A horizon line located in the middle of the image, dividing it in two equal halves, can produce an uncomfortable duality, especially if it's dead straight. In this work the seabirds and white wavecrests, though insignificant in terms of the painting area, provide a unifying third element. Of course, there may be instances where a painter wants to create an unnerving, unresolved visual tension in a painting.

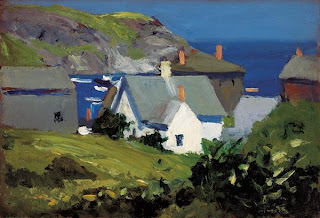

I posted this work because of the rich emerald and jade hues in the waves, and the fine brushwork. It came from an auction website with very little info.

+c+1928+Aust.jpg)